Alison Bashford

In real time, it was geologically slow. But now we can enjoy the breakup of Gondwanaland as a moment’s internet entertainment on computer-generated imagery: 200 million years or so, in 60 seconds. Watching one such reconstruction, YouTube viewers respond with sweetly humanized continents “breaking up”:

Africa: i quit i wanna be my own continent. South america: yeah me to im going with north America. India: hello asia. Australia: its up to you antartica. Antartica: why:(

“Earth” finds the break-up too painful: “do you even know how much it hurts.” But “Penguin” is happy: “Yay my home formed.” Another viewer, however, gets more serious and doesn’t want to play; all the flippant nonsense is brought back to earth. “Cool CGI … but I’m pretty sure this never happened.”[1]

Presenting whimsical twenty-first century responses to Gondwanaland is more than a conceit. This self-consciously re-imagined earth-relationship follows a long modern tradition of fictionalising, re-enchanting, and even sacralising supercontinents and earth break ups. Gondwanaland has been proactively imagined and re-imagined, even by those who claim it never existed. And so, there is a cultural history of modern Gondwanaland to trace, one element of our new histories of and for an ancient continent. Gondwanaland appears time and again within science fiction, for example, and as children’s geological fantasias of deep time.

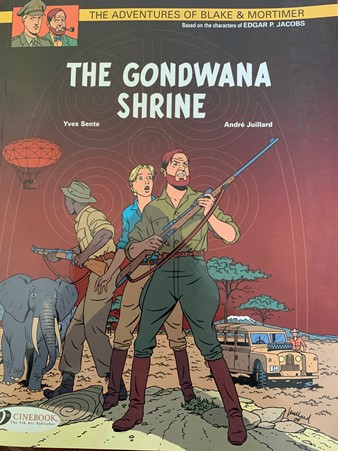

In J. B. Rowley’s contemporary children’s series, Trapped in Gondwana, protagonists fall through cracks in the earth. “Gondwana” in this children’s fantasy is forested and spirited and folkloric. But it is resolutely not home, even if the centre of Gondwana is the quest place of magic release, a kind of land bridge to home. It is a difficult read, given the wider geopolitics of Gondwana: the present-day Gond land-claims in Central India. We know that even as this fantastic forest Gondwana is conjured as anti-home, as alien other-place, a Gondwana homeland movement is hard at work trying to establish a state-recognized home, sometimes with reference to a “Gondwanaland” that is also imagined and mythic, if in a different register and with much higher stakes. In Yves Sente’s comic Le sanctuaire du Gondwana (2008) we are taken, once again, far inside the earth, through a secret entrance inside the lake-crater of an old volcano in Tanzania. This is a Mortimer and Blake paleo series that includes in this instance, and strangely, the characters of Mr and Mrs Leaky, paleontologists. In this rendition, the centre of Gondwana is also a quest-place. The Gondwana Shrine marks an origin of anthropocentric life. Raiding mythic and real geologies, and academic disciplines that deal with space and time—archeology, paleoanthropology, geology—Le sanctuaire du Gondwana follows Atlantis Mystery (1957), The Time Trap (1962), and the Sarcophogi of the Sixth Continent (2003). Perhaps it was only a matter of time before ‘Gondwana” was discovered and deployed.

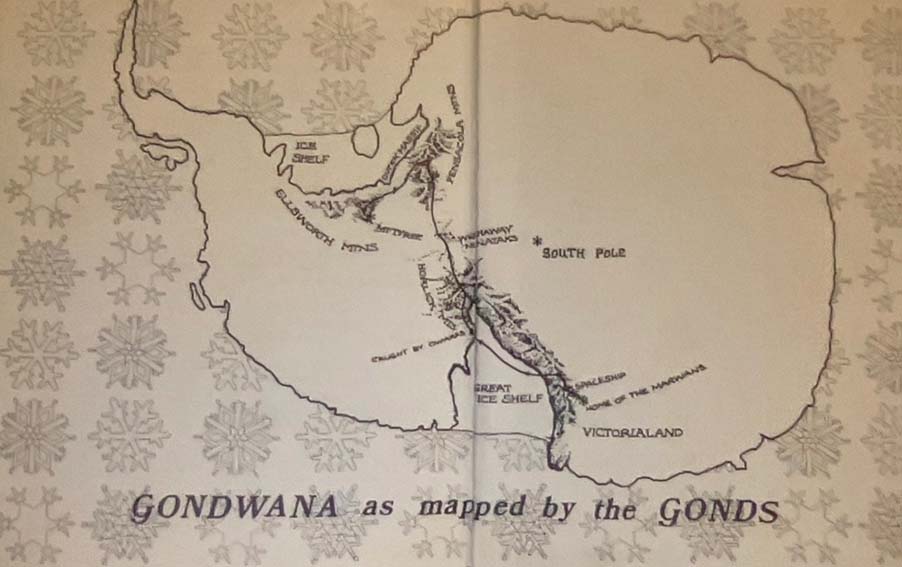

Elsewhere in its modern cultural diaspora, “Gondwana” comes to stand for “Antarctica.” In yet another children’s story, not only is Gondwana actually the name of a fantasy Antarctica, but the protagonist children actually meet “Gonds,” who are cast now as the indigenous people of the icy continent. “Gondwana as mapped by the Gonds” is the frontispiece, a familiar quest-map, but bizarrely also a map of present-day Antarctica. When the children find themselves in this strange and icy place, a “Gond” explains: “This is Victoria Land, on what we call Gondwana, part of the most ancient continent of Earth.” In the chapter, “In which the children meet a Gond,” they are told definitively that it’s not Antarctica. “Gondwana is the name of this ancient place, the country of my people. It wasn’t always as you see it now. It was once free of snow and ice—quite a hot place in fact, where lovely flowers and trees grew and bountiful rivers flowed to the sea.”[2] The peopling of Antarctica with its own indigenous people is perhaps the greatest fantasy of all.

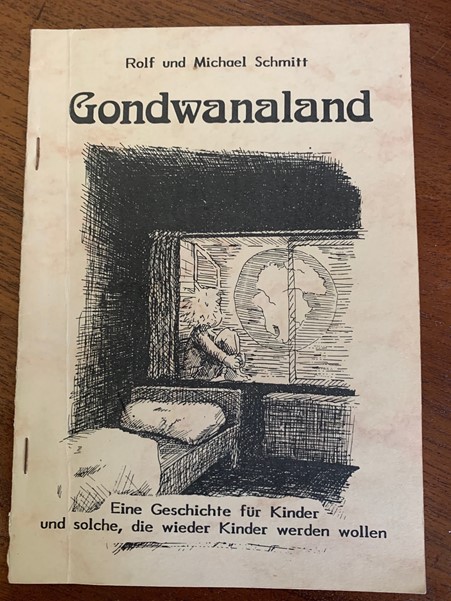

Gondwanaland reappears in German storytelling of the 1980s as well, again linked broadly to an environmentalist ethics, overlaid with a pacifist and anti-nuclear politics of that decade. A German fantasia “Gondwanaland” (1986) is subtitled, “for children and those who want to become children again.” It is the opposite of dangerous place-time in this rendition. Far from being an anti-home, “Gondwanaland” is the ideal and aspirational home for the family-of all-humanity, united in its difference.

Far from Gondwanaland being found deep inside the Earth, here it is found in the full moon, and in the protagonists’ boyhood dreaming. Here, Gondwanaland is utterly human. It stands for One World, environmental cosmopolitanism 1980s-style. Gondwanaland’s “environmentalism” in this German version is linked far more to an anti-nuclear and anti-war politics of the 1980s than a wilderness/nature-quest that governed Australian environmentalism in the same decade.

Alison Bashford, ‘Gondwanaland Fictions’ will appear in full in Alison Bashford, Adam Bobbette and Emily Kern (eds), New Earth Histories (University of Chicago Press, forthcoming).

[1] Comments on “Gondwanaland Break up” Mawson’s Huts Foundation, September 3, 2019, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s9gHLs7QeTw.

[2] Margaret Andrew, Flight to Antarctica (Cambridge: Burlington Press, 1985), 15-18.