Alessandro Antonello

The geological and human histories of Antarctica and Gondwanaland are intimately linked.

East Antarctica was at the heart of Gondwanaland when it began to form over 600 million years ago. And while the Pangea and Gondwanaland breakups began around 180 million years ago, it was not until the Eocene-Oligocene transition around 34 million years ago that Antarctica came to be fully separated from its other southern siblings. Once that separation happened, the Southern Ocean’s circumpolar currents began to move, and ice sheets began to form on the Antarctic continent.

The late nineteenth century search for specimens proving or disproving the existence of a massive southern continent—what Eduard Suess and WT Blanford called Gondwanaland—also shaped some of the earliest scientific work on the Antarctic continent.

It was only at the beginning of the twentieth century that major scientific expeditions finally worked on the Antarctic continent. The British explorers going south took The Antarctic Manual, a collection of literature reviews on the contemporary state of relevant scientific knowledge as well as instructions for specimens and data to collect.

Their geological instructions came from William Thomas Blanford. A venerable geologist, Blanford had worked extensively for the British imperial Geological Survey of India and had been a foundational thinker about Gondwana geologies. Blanford noted that the “distribution of sea and land in the Southern Hemisphere in former periods” was an important question which Antarctic specimens could illuminate. The Antarctic explorers should keep their eyes peeled for Glossopteris specimens. Glossopteris was a small plant that lived in boggy, mire landscapes during the Permian period, and which would illuminate the connections between southern lands.

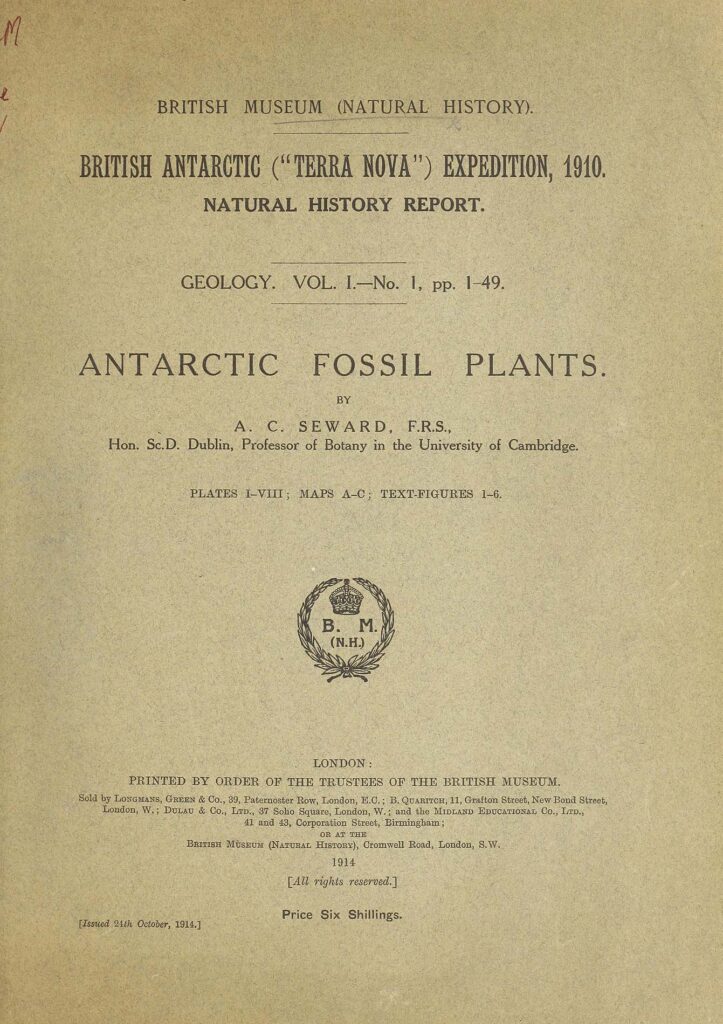

Luckily, some early Antarctic explorers did find Glossopteris. But that discovery came with tragedy too. On his Terra Nova Expedition (1911–13), Robert Scott was hoping to be the first person to reach the South Pole. He was narrowly beaten by Roald Amundsen and died with his team on the return journey from the pole. Scott and his team, on their return, stopped to do geological work at Buckley Island near the Beardmore Glacier. They kept the specimens from that site even as they got rid of excess weight in the hope of surviving their trek. Eventually those specimens made it back to London, where the prominent paleobotanist Albert Seward analysed them. He concluded that it was “difficult to escape from the conclusion that the ancient continent of Gondwana extended to within a short distance of the South Pole or even to the Pole itself, whether as a continuous continent or as an archipelago of islands cannot be determined.”

Decades later, Gondwanaland would also animate an interesting moment of Antarctic geopolitics. In the intervening time, Gondwanaland went from being a speculative southern continent existing in the content of land bridges and ocean floor subsidence, to being a more accepted geological fact in the context of a revolution in the earth sciences culminating in the accepted theory of plate tectonics.

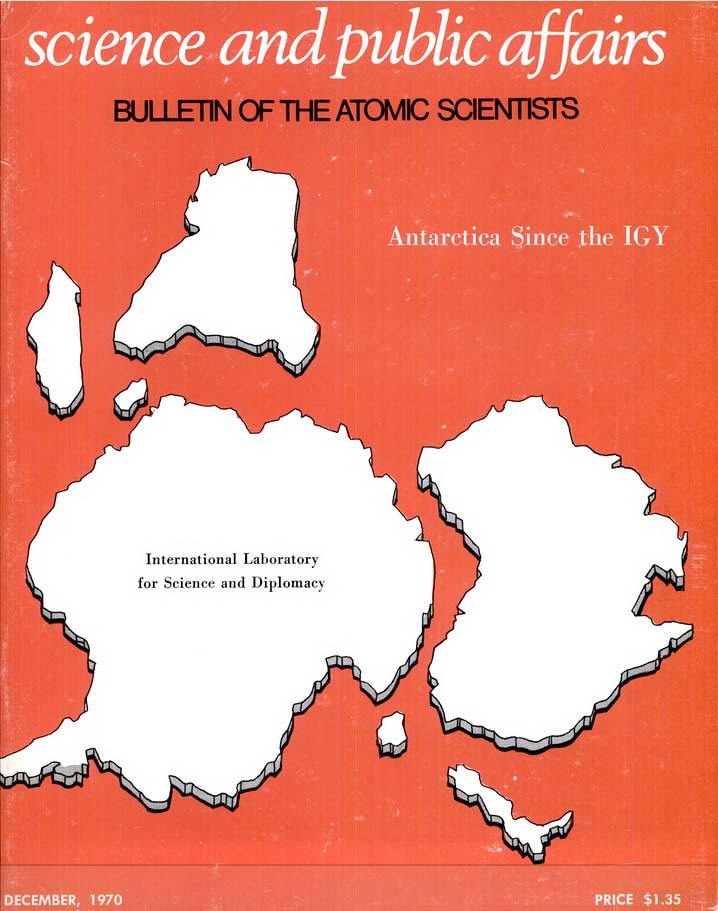

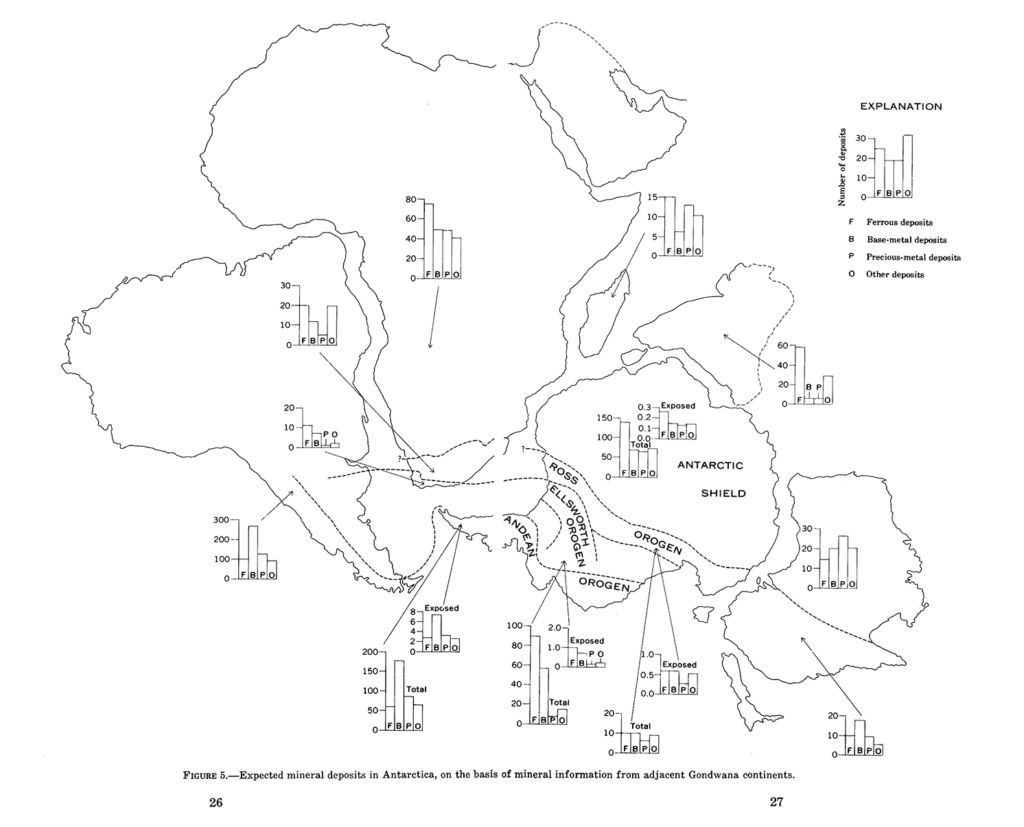

From the late 1960s into the 1970s, many countries and commercial actors wondered if there might be exploitable mineral and oil resources in Antarctica. Gondwanaland was brought into these discussions. The basic point was: if Antarctica’s old Gondwana siblings like Australia and southern Africa were resource rich, why shouldn’t Antarctica also be filled with valuable minerals? Visualisations of these supposed resource histories were published in prominent and influential publications. In the midst of the Cold War, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists was a prominent publication with international reach: putting Antarctica-with-Gondwana connections on its cover in December 1970 spoke to internationalism, but in its pages also spoke to exploitation. A major 1974 report from the United States Geological Survey on Antarctic mineral resources also used the Gondwanaland figure to estimate and suggest mineral prospectivity. This report circulated widely in Antarctic geopolitical circles at the time.

These are only two episodes from Antarctica and Gondwanaland’s linked modern histories. There is still much to be learned about how geologists and earth scientists across the twentieth century have understood the geological history of Gondwanaland and Antarctica’s place in it. There is still also much to learn about the interesting and curious ways that Antarctica and Gondwanaland have been linked in popular cultures and geo-politics.

An essay on the modern histories and cultures of Antarctica and Gondwanaland by Alessandro Antonello will appear in the forthcoming “Real Cool World” issue of Griffith Review.